Syria has faced a chorus of criticism over its eight-month crackdown on opposition protesters that has left, according to sources reporting to the U.N., at least 3,500 people dead. The regime is showing no indication it will soften its position, so will President Bashar al-Assad be open to any outside influence?

Who is criticizing Syria?

Many Western powers, notably the United States, Britain and France have condemned Syria's brutal crackdown. The regime shrugged off that criticism, but in a surprise move, 18 of the Arab League's 22 members voted on November 12 to suspend Damascus' membership of the alliance.

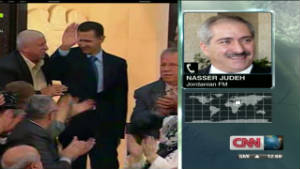

On Monday Jordan's King Abdullah said he would step down if he were al-Assad, a statement observers interpreted as a call for the Syrian president to do just that.

Turkey also added to the pressure Tuesday, threatening to cut off power supplies if Syria did not change course.

This criticism from regional neighbors previously considered allies is a stinging blow to al-Assad, according to Professor Fawaz Gerges, Professor of Middle Eastern Politics and International Relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

"Externally Syria is now more isolated than ever," Gerges told CNN. "The noose is now tightening around the neck of the regime. The loss of Turkey is a huge blow: not only are the two countries important trading partners but al-Assad and Turkish leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan used to be friends -- they even took vacations together. This was not just a political relationship -- it was one based on tremendous potential between the two countries."

The Arab League's move though was the biggest shock. Gerges said its decision to suspend Syria was a "game-changer," as Syria portrays itself as the "beating heart of Arab nationalism." Consequently "the Arab League's decision resonates hugely among the Syrian people," Gerges said.

Will Syria listen to any of this external criticism?

This is the big question. According to another analyst, the regime has isolated itself internationally and is, on the face of it, taking little notice of criticism. "They think it's possible to survive on their own for a considerable amount of time until it blows over," said Chris Phillips, from the Economist Intelligence Unit. "They're relatively self-sufficient in terms of food, and they believe the Arab League won't impose such hefty sanctions as to threaten this. But they are aware that more active moves to topple them -- military or economic -- will make it difficult for them particularly if they get the U.N. to sign off on them."

The reported release of 1,000 political prisoners, Gerges said, could be an indication that the Syrian regime still believes it can influence its neighbors. What effect these external factors have on the internal dynamic is an unknown quantity though. While "the external war has been lost," internally the regime remains fairly strong, he added.

What effect would a trade embargo on Syria have?

Wide-ranging sanctions were imposed on Iraq for more than a decade, but they failed to bring down President Saddam Hussein; he was only toppled by the U.S.-backed invasion of 2003.

Syrian opposition activists are better organized than those in Iraq under Hussein, said Phillips. Sanctions could threaten the regime though if they make it harder to pay soldiers' wages: during the Libyan revolution, for example, unpaid soldiers deserted, putting extra pressure on leader Moammar Gadhafi.

The noose is now tightening around the neck of the regime. The loss of Turkey is a huge blow.

Professor Fawaz Gerges, from London School of Economics

Professor Fawaz Gerges, from London School of Economics

So can anyone influence Syria?

Russia and Iran are important factors in influencing Syria's behavior, Phillips said.

Moscow has been an ally since the Cold War and Russia's only naval base in the Mediterranean, Tartous, is in Syria. During the crisis Russia has accused the West of inciting opposition to the al-Assad government. The Kremlin is loath to back the West's position on Syria, he said, due to a feeling that its stance on Libya was misinterpreted. When Moscow declined to use its U.N. Security Council veto to block NATO military action, this was painted by some in the West as Russia giving its support to the Libyan operation.

On Tuesday Russia's foreign ministry said that it had not changed its position on Syria's political crisis, it urged all opposition groups to renounce violence and engage in peaceful dialogue with the government.

Iran is an even more important ally of Syria. Tehran has traditionally seen Syria as a gateway to the Arab world and a key supply link to its Lebanese ally Hezbollah, said Gerges. "So it's significant that Iran is reported to be establishing links to Syrian opposition groups. Even Iran is now trying to rescue its own interests."

China also used its Security Council veto to block a U.N. resolution condemning Syria, but its position is considered to be less solid than that of Russia, Phillips believes.

Despite these links, Syria is unlikely to take much notice of any of these countries. "Even if Russia said al-Assad should step down, I don't think he would," he added.

What lies behind the Arab League's move?

On one level, the Arab League is keen not to be on the wrong side of history, said Phillips. "By and large it is against popular revolutions, so the vote to suspend Syria's membership shows that it has seen the shift in public opinion, and wants to project this to its people and the wider world."

CNN's veteran Middle East correspondent Ben Wedeman sees the move in the context of the geopolitical shift during the last decade, which has seen Iran's power and influence surge.

The uprising in Syria went a long way to undercut Iran's oldest and most reliable Arab ally in Damascus, and Saturday's vote to suspend Syria from the Arab League was an added bonus.

CNN's Ben Wedeman

CNN's Ben Wedeman

"The U.S. economy -- and thus, its political clout -- is in decline," Wedeman wrote in response to Saturday's move by the Arab League. "Increasingly, America is viewed in the Middle East as an economically bankrupt, militarily and diplomatically overextended, withering superpower. In short, a huge vacuum looms in the region, and Iran could be the chief beneficiary.

"Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf states are alarmed, and are eager to cut Iran down to size. The uprising in Syria went a long way to undercut Iran's oldest and most reliable Arab ally in Damascus, and Saturday's vote to suspend Syria from the Arab League was an added bonus. Syria is now isolated more than ever before, which means Iran's other allies in the region -- Hamas and Hezbollah -- could suffer, too."

How much credibility does the Arab League have?

The 66-year-old Arab League is seen by many in the Arab world as a toothless organization, said Phillips, who argues that this is why its vote to suspend Syria is so surprising. "The move does not mean it's reinventing itself. The Arab League will still be seen as the agent of brutal, corrupt regimes: of the 22 Arab League member states only three members are even vaguely democratic, and of them only Tunisia has had internationally recognized free and fair elections.

"But the decision does show that now the Gulf states may have to start recognizing the power of the ballot box in its relations with neighbors."

Why did Jordan's King Abdullah effectively call for al-Assad to quit?

Jordan has also been facing protests in the last eight months. King Abdullah's statement does not represent a genuine belief in democracy, but he is aware of the legitimacy of calling for Assad to go. He is doing it for two reasons: on the one hand he wants to realign Jordan with the West; on the other he knows the Jordanian population feels for their oppressed Syrian "cousins."

There is an opposition movement in Jordan -- if a more modest one than in Syria -- the difference is in how the governments have responded. Jordan did not respond with brute force as Assad did; and King Abdullah has appointed a new prime minister who has an image as a reformer.

What role if any does religion play in the crisis?

President al-Assad belongs to the Alawite sect while Sunni Muslims form the majority in Syria. However, the crisis should not be seen solely in sectarian terms, Gerges said. "Essentially this is a political struggle, although al-Assad is imposing a sectarian element to it. Many Syrians have been sitting on the sidelines, worried about the descent into armed sectarian violence."

But Gerges fears a "nuclear scenario" in the country as the violence intensifies. "Al-Assad has effectively asked his people: Do you want Syria to be another Iraq or Lebanon -- racked by sectarian divides? But everyone is now calling his bluff."

So what happens next?

Most analysts see little prospect of a peaceful resolution to the crisis, with al-Assad remaining resistant to all external pressure. "This is the beginning of the armed struggle in Syria," said Gerges. "If the political option is now shut down there will be a prolonged conflict ahead."

But armchair strategists should be wary of making too many predictions. Last month, Ed Husain, a Senior Fellow for Middle Eastern Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, wrote this cautionary piece of analysis. "The first rule for those observing political developments in the modern Middle East is that nothing is as it seems at first sight. Political calculations that make sense in Washington, DC, London, or Paris do not always translate so well on the ground.

"From the Balfour Declaration of 1917 to the Suez crisis of 1956 to the Hamas victory in 2006 in Gaza, Westerners often fail to grasp the complicated, counterintuitive reality of life in the Arab world."

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten